|

Zovia 1/35E-21

Zovia 1/35E-28

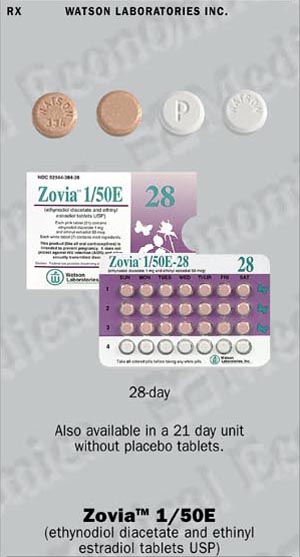

Zovia 1/50E-21

Zovia 1/50E-28

(Ethynodiol Diacetate and Ethinyl Estradiol Tablets, USP)

Patients should be counseled that this product does not protect against HIV infection (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases.

Zovia 1/35E-21 and Zovia 1/35E-28. Each light pink tablet contains 1 mg of ethynodiol diacetate and 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol, and the inactive ingredients include microcrystalline cellulose, lactose (anhydrous), magnesium stearate, polacrilin potassium and povidone. In addition, the coloring agents are D&C Yellow No. 10 and D&C Red No. 30. Each white tablet in the Zovia 1/35E-28 package is a placebo containing no active ingredients and the inactive ingredients include microcrystalline cellulose, lactose (anhydrous) and magnesium stearate.

Zovia 1/50E-21 and Zovia 1/50E-28. Each pink tablet contains 1 mg of ethynodiol diacetate and 50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol, and the inactive ingredients iinclude microcrystalline cellulose, lactose (anhydrous), magnesium stearate, polacrilin piotassium and povidone. In addition, the coloring agents are D&C Yellow No. 10 and D&C Red No. 30. Each white tablet in the Zovia 1/50E-28 package is a placebo containing no active ingredients, and the inactive ingredients include microcrystalline cellulose, lactose (anhydrous) and magnesium stearate.

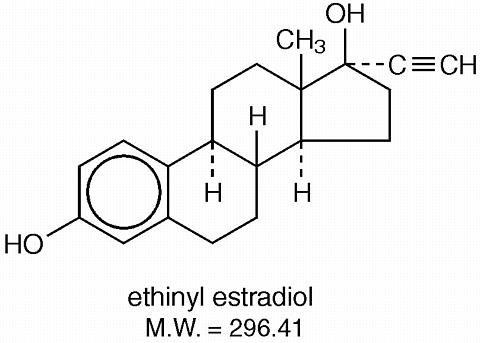

The chemical name for ethynodiol diacetate is 19-nor-17(alpha)-pregn-4-en-20-yne-3(beta), 17-diol diacetate, and for ethinyl estradiol it is 19-nor-17(alpha)-pregn-1, 3, 5 (10)-trien-20-yne-3, 17-diol. The structural formulas are as follows:

Therapeutic class: Oral contraceptive

|

|

Combination oral contraceptives act primarily by suppression of gonadotropins. Although the primary mechanism of this action is inhibition of ovulation, other alterations in the genital tract, including changes in the cervical mucus (which increase the difficulty of sperm entry into the uterus) and the endometrium (which may reduce the likelihood of implantation) may also contribute to contraceptive effectiveness.

Zovia 1/35E and Zovia 1/50E are indicated for the prevention of pregnancy in women who elect to use oral contraceptives as a method of contraception.

Oral contraceptives are highly effective. Table 1 lists the typical accidental pregnancy rates for users of combination oral contraceptives and other methods of contraception. The efficacy of these contraceptive methods, except sterilization and progestogen implants and injections, depends upon the reliability with which they are used. Correct and consistent use of methods can result in lower failure rates.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Oral contraceptives should not be used in women who have the following conditions:

| Cigarette smoking increases the risk of serious cardiovascular side effects from oral contraceptive use. This risk increases with age and with heavy smoking (15 or more cigarettes per day) and is quite marked in women over 35 years of age. Women who use oral contraceptives should be strongly advised not to smoke. |

The use of oral contraceptives is associated with increased risk of several serious conditions including venous and arterial thromboembolism, thrombotic and hemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction, liver tumors or other liver lesions, and gallbladder disease. The risk of morbidity and mortality increases signficantly in the presence of other risk factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, obesity, and diabetes mellitus.

Practitioners prescribing oral contraceptives should be familiar with the following information relating to these and other risks.

The information contained herein is principally based on studies carried out in patients who use oral contraceptives with formulations containing higher amounts of estrogens and progestogens than those in common use today. The effect of long-term use of the oral contraceptives with lesser amounts of both estrogens and progestogens remains to be determined.

Throughout this labeling, epidemiological studies reported are of two types: retrospective case-control studies and prospective cohort studies. Case-control studies provide an estimate of the relative risk of a disease, which is defined as the ratio of the incidence of a disease among oral contraceptive users to that among nonusers. The relative risk (or odds ratio) does not provide information about the actual clinical occurrence of a disease. Cohort studies provide a measure of both the relative risk and the attributable risk. the latter is the difference in the incidence of disease between oral contraceptive users and nonusers. The attributable risk does provide information about the actual occurrence or incidence of a disease in the subject population. For further information, the reader is referred to a text on epidemiological methods.

a. Myocardial infarction. An increased risk of myocardial infarction has been associated with oral contraceptive use. 2-21 This increased risk is primarily in smokers or in women with other underlying risk factors for coronary artery disease such as hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and hypercholesterolemia. The relative risk for myocardial infarction in current oral contraceptive users has been estimated to be 2 to 6. The risk is very low under the age of 30. However, there is the possibility of a risk of cardiovascular disease even in very young women who take oral contraceptives.

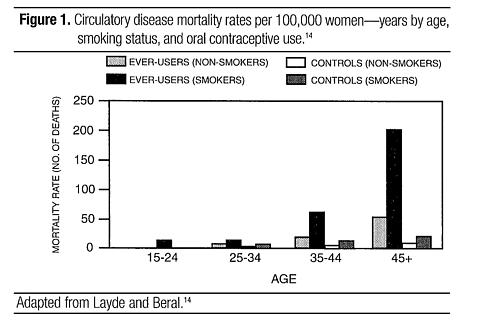

Smoking in combination with oral contraceptive use has been reported to contribute substantially to the risk of myocardial infarction in women in their mid-thirties or older, with smoking accounting for the majority of excess cases. 22 Mortality rates associated with circulatory disease have been shown to increase substantially in smokers, especially in those 35 years of age and older among women who use oral contraceptives (see Figure 1, Table 2).

|

Oral contraceptives may compound the effects of well-known cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemias, hypercholesterolemia, age, cigarette smoking, and obesity. In particular, some progestogens decrease HDL cholesterol 23-31 and cause glucose intolerance, while estrogens may create a state of hyperinsulinism. 32 Oral contraceptives have been shown to increase blood pressure among some users (see WARNING No. 9). Similar effects on risk factors have been associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

b. Thromboembolism. An increased risk of thromboembolic and thrombolic disease associated with the use of oral contraceptives is well established. 17, 33-51 Case-control studies have estimated the relative risk to be 3 for the first episode of superficial venous thrombosis, 4 to 11 for deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, and 1.5 to 6 for women with predisposing conditions for venous thromboembolic disease. 34-37, 45, 46 Cohort studies have shown the relative risk to be somewhat lower, about 3 for new cases (subjects with no past history of venous thrombosis or varicose veins) and about 4.5 for new cases requiring hospitalization. 42, 47, 48 The risk of venous thromboemblic disease associated with oral contraceptives is not related to duration of use.

A two- to seven-fold increase in relative risk of postoperative thromboembolic complications has been reported with the use of oral contraceptives. 38, 39 The relative risk of venous thrombosis in women who have predisposing conditions is about twice that of women without such medical conditions. 43 If feasible, oral contraceptives should be discontinued at least 4 weeks prior to and for 2 weeks after elective surgery of a type associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, and also during and following prolonged immobilization. Since the immediate postpartum period is also associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism, oral contraceptives should be started no earlier than 4 to 6 weeks after delivery in women who elect not to breast feed.

c. Cerebrovascular diseases. Both the relative and attributable risks of cerebrovascular events (thrombotic and hemorrhagic strokes) have been reported to be increased with oral contraceptive use, 14, 17, 18, 34, 42, 46, 52-59 although, in general, the risk was greatest among older (over 35 years) hypertensive women who also smoked. Hypertension was reported to be a risk factor for both users and nonusers, for both types of strokes, while smoking increased the risk for hemorrhagic strokes.

In one large study, 52 the relative risk for thrombotic stroke was reported as 9.5 times greater in users than in nonusers. It ranged from 3 for normotensive users to 14 for users with severe hypertension. 54 The relative risk for hemorrhagic stroke was reported to be 1.2 for nonsmokers who used oral contraceptives, 1.9 to 2.6 for smokers who did not use oral contraceptives, 6.1 to 7.6 for smokers who used oral contraceptives, 1.8 for normotensive users, and 25.7 for users with severe hypertension. The risk is also greater in older women and among smokers.

d. Dose-related risk of vascular disease with oral contraceptives. A positive association has been reported between the amount of estrogen and progestogen in oral contraceptives and the risk of vascular disease. 41, 43, 53, 59-64 A decline in serum high density lipoproteins (HDL) has been reported with many progestogens. 23-31 A decline in serum high density lipoproteins has been associated with an increased incidence of ischemic heart disease. 65 Because estrogens increase HDL-cholesterol, the net effect of an oral contraceptive depends on the balance achieved between doses of estrogen and progestogen and the nature and absolute amount of progestogens used in the contraceptives. The amount of both steroids should be considered in the choice of an oral contraceptive.

Minimizing exposure to estrogen and progestogen is in keeping with good principles of therapeutics. For any particular estrogen-progestogen combination, the dosage regimen prescribed should be one that contains the least amount of estrogen and progestogen that is compatible with a low failure rate and the needs of the individual patient. New acceptors of oral contraceptives should be started on preparations containing the lowest estrogen content that produces satisfactory results in the individual.

e. Persistance of risk of vascular disease. There are three studies that have shown persistence of risk of vascular disease for users of oral contraceptives. In a study in the United States, the risk of developing myocardial infarction after discontinuing oral contraceptives persisted for at least 9 years for women 40-49 years old who had used oral contraceptives for 5 or more years, but this increased risk was not demonstrated in other age groups. 16 Another American study reported former use of oral contraceptives was significantly associated with increased risk of subaracnoid hemorrhage. 57 In another study, in Great Britain, the risk of developing nonrheumatic heart disease plus hypertension, subarachnoid hemorrhage, cerebral thrombosis, and transient ischemic attacks persisted for at least 6 years after discontinuation of oral contraceptives, although the excess risk was small. 14, 18, 66 It should be noted that these studies were performed with oral contraceptive formulations containing 50 mcg or more of estrogens.

2. Estimates of mortality from contraceptive use. One study 67 gathered data from a variety of sources that have estimated the mortality rates associated with different methods of contraception at different ages. (Table 2). These estimates include the combined risk of death associated with contraceptive methods plus the risk attributable to pregnancy in the event of method failure. Each method of contraception has its specific benefits and risks. The study concluded that, with the exception of oral contraceptive users 35 and older who smoke and 40 or older who do not smoke, mortality associated with all methods of birth control is low and below that associated with childbirth. The observation of a possible increase in risk of mortality with age of oral contraceptive users is based on data gathered in the 1970's, but not reported until 1983. 67 However, current clinical practice involves the use of lower estrogen dose formulations combined with careful restriction of oral contraceptive use to women who do not have the various risk fators listed in this labeling.

Because of these changes in practice and, also, because of some limited new data that suggest that the risk of cardiovascular disease with the use of oral contraceptives may now be less than previously observed, 48, 152 the Fertility and Maternal Health Drugs Advisory Committee was asked to review the topic in 1989. The Committee concluded that, although cardiovascular disease risks may be increased with oral contraceptive use after age 40 in healthy nonsmoking women (even with the newer low-dose formulations), there are greater potential health risks associated with pregnancy in older women and with the alternative surgical and medical procedures that may be necessary if such women do not have access to effective and acceptable means of contraception.

Therefore, the Committee recommended that the benefits of oral contraceptive use by healthy nonsmoking women over 40 may outweigh the possible risks. Of course, older women, as all women who take oral contraceptives, should take the lowest possible dose formulation that is effective.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3. Carcinoma of the breast and reproductive organs. Numerous epidemiological studies have been performed on the incidence of breast, endometrial, ovarian, and cervical cancer in women using oral contraceptives. While there are conflicting reports, most studies suggest that the use of oral contraceptives is not associated with an overall increase in the risk of developing breast cancer. 17, 40, 68-78 Some studies have reported an increased relative risk of developing breast cancer, particularly at a young age. 79-102, 151 This increased relative risk appears to be related to duration of use.

Some studies suggested that oral contraceptive use was associated with an increase in the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, dysplasia, erosion, carcinoma, or microglandular dysplasia in some populations of women. 17, 50, 103-115 However, there continues to be controversy about the extent to which such findings may be due to differences in sexual behavior and other factors.

In spite of many studies of the relationship between oral contraceptive use and breast and cervical cancers, a cause and effect relationship has not been established.

4. Hepatic neoplasia. Benign hepatic adenomas and other hepatic lesions have been associated with oral contraceptive use, 116-121 although the incidence of such benign tumors is rare in the United States. Indirect calculations have estimated the attributable risk to be in the range of 3.3 cases per 100,000 for users, a risk that increases after 4 or more years of use. 120 Rupture of benign, hepatic adenomas or other lesions may cause death through intraabdominal hemorrhage. Therefore, such lesions should be considered in women presenting with abdominal pain and tenderness, abdominal mass, or shock. About one quarter of the cases presented because of abdominal masses, up to one half had signs and symptoms of acute intraperitoneal hemorrhage. 121 Diagnosis may prove difficult.

Studies from the U.S., 122, 150 Great Britain, 123, 124 and Italy 125 have shown an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in long-term (>8 years; relative risk of 7-20) oral contraceptive users. However, these cancers are rare in the United States, and the attributable risk (the excess incidence) of liver cancers in oral contraceptive users approaches less than 1 per 1,000,000 users.

5. Ocular lesions. There have been reports of retinal thrombosis and other ocular lesions associated with the use of oral contraceptives. Oral contraceptives should be discontinued if there is unexplained, gradual or sudden, partial or complete loss of vision; onset of proptosis or diplopia; papilledema; or any evidence of retinal vascular lesions. Appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures should be undertaken immediately.

6. Oral contraceptive use before or during pregnancy. Extensive epidemiological studies have revealed no increased risk of birth defects in women who have used oral contracepties prior to pregnancy. 126, 129 The majority of recent studies also do not suggest a teratogenic effect, particularly insofar as cardiac anomalies and limb reduction defects are concerned, 126, 129 when the pill is taken inadvertently during early pregnancy.

The administration of oral contraceptives to induce withdrawal bleeding should not be used as a test for pregnancy. Oral contraceptives should not be used during pregnancy to treat threatened or habitual abortion. It is recommended that for any patient who has missed two consecutive periods, pregnancy should be ruled out before continuing oral contraceptive use. If the patient has not adhered to the prescribed schedule, the possibility of pregnancy should be considered at the time of the first missed period and further use of oral contraceptives should be withheld until pregnancy has been ruled out. Oral contraceptive use should be discontinued if pregnancy is confirmed.

7. Gallbladder disease. Earlier studies reported an increased lifetime relative risk of gallbladder surgery in users of oral contraceptives and estrogens. 40, 42, 53, 70 More recent studies, however, have shown that the relative risk of developing gallbladder disease among oral contraceptive users may be minimal. 130-132 The recent findings of minimal risk may be related to the use of oral contraceptive formulations containing lower doses of estrogens and progestogens.

8. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolic effects. Oral contraceptives have been shown to cause a decrease in glucose tolerance in a signficant percentage of users. 32 This effect has been shown to be directly related to estrogen dose. 133 Progestogens increase insulin secretion and create insulin resistance, the effect varying with different progestational agents. 32, 134 However, in the nondiabetic woman, oral contraceptives appear to have no effect on fasting blood glucose. Because of these demonstrated effects, prediabetic and diabetic women should be carefully observed while taking oral contraceptives.

Some women may have persistent hypertriglyceridemia while on the pill. As discussed earlier (see 1a and 1d ), changes in serum triglycerides and lipoprotein levels have been reported in oral contraceptive users. 23-31, 135, 136

9. Elevated blood pressure. An increase in blood pressure has been reported in women taking oral contra-ceptives 50, 53, 137-139 and this increase is more likely in older oral contraceptive users 137 and with extended duration of use. 53 Data from the Royal College of General Practitioners 138 and subsequent randomized trials have shown that the incidence of hypertension increases with increasing concentration of progestogens.

Women with a history of hypertension or hypertension-related disease, or renal disease 139 should be encouraged to use another method of contraception. If such women elect to use oral contraceptives, they should be monitored closely and if significant elevation of blood pressure occurs, oral contraceptives should be discontinued. For most women, elevated blood pressure will return to normal after stopping oral contraceptives, 137 and there is no difference in the occurrence of hypertension among ever- and never-users. 140

10. Headache. The onset or exacerbation of migraine or the development of headache of a new pattern that is recurrent, persistent, or severe requires discontinuation of oral contraceptives and evaluation of the cause.

11. Bleeding irregularities. Breakthrough bleeding and spotting are sometimes encountered in patients on oral contraceptives, especially during the first three months of use. Nonhormonal causes should be considered and adequate diagnostic measures taken to rule out malignancy or pregnancy in the event of breakthrough bleeding, as in the case of any abnormal vaginal bleeding. If a pathologic basis has been excluded, time alone or a change to another formulation may solve the problem. In the event of amenorrhea, pregnancy should be ruled out.

1. Physical examination and follow-up. It is good medical practice for all women to have annual history and physical examinations, including women using oral contraceptives. The physical examination, however, may be deferred until after initiation of oral contraceptives if requested by the woman and judged appropriate by the clinician. The physical examination should include special reference to blood pressure, breasts, abdomen, and pelvic organs, including cervical cytology, and relevant laboratory tests. In case of undiagnosed, persistent, or recurrent abnormal vaginal bleeding, appropriate diagnostic measures should be conducted to rule out malignancy. Women with a strong family history of breast cancer or who have breast nodules should be monitored with particular care.

2. Lipid disorders. Women who are being treated for hyperlipidemias should be folowed closely if they elect to use oral contraceptives. Some progestogens may elevate LDL levels and may render the control of hyperlipidemias more difficult.

3. Liver function. If jaundice develops in any woman receiving oral contraceptives, they should be discontinued. Steroids may be poorly metabolized in patients with impaired liver function and should be administered with caution in such patients. Cholestatic jaundice has been reported after combined treatment with oral contraceptives and troleandomycin. Hepatotoxicity following a combination of oral contraceptives and and cyclosporine has also been reported.

4. Fluid retention. Oral contraceptives may cause some degree of fluid retention. They should be prescribed with caution, and only with careful monitoring, in patients with conditions that might be aggravated by fluid retention, such as convulsive disorders, migraine syndrome, asthma, or cardiac, hepatic, or renal dysfunction.

5. Emotional disorders. Women with a history of depression should be carefully observed and the drug discontinued if depression recurs to a serious degree.

6. Contact lenses. Contact lens wearers who develop visual changes or changes in lens tolerance should be assessed by an ophthalmologist.

7. Drug Interactions. Reduced efficacy and increased incidence of breakthrough bleeding and menstrual irregularities have been associated with concomitant use of rifampin. A similar association, though less marked, has been suggested for barbiturates, phenylbutazone, phenytoin sodium, and possibly with griseofulvin, ampicillin, and tetracyclines.

8. Laboratory test interactions. Certain endocrine and liver function tests and blood components may be affected by oral contraceptives:

9. Carcinogenesis. See .

10. Pregnancy. Pregnancy Category X. See CONTRAINDICATIONS and .

11. Nursing mother. Small amounts of oral contraceptive steroids have been identified in the milk of nursing mothers 141-143 and a few adverse effects on the child have been reported, including jaundice and breast enlargement. In addition, oral contraceptives give in the postpartum period may interfere with lactation by decreasing the quantity and quality of breast milk. If possible, the nursing mother should be advised not to use oral contraceptives, but to use other forms of contraception until she has completely weaned her child.

12. Venereal diseases. Oral contraceptives are of no value in the prevention or treatment of venereal disease. The prevalence of cervical Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in oral contraceptive users is increased several-fold. 144, 145 It should not be assumed that oral contraceptives afford protection against pelvic inflammatory disease from chlamydia. 144 Patients should be counseled that this product does not protect against HIV infection (AIDS) and other sexually transmitted diseases.

13. General.

See patient labeling printed below.

An increased risk of the following serious adverse reactions has been associated with the use of oral contraceptives (see ):

There is evidence of an association between the following conditions and the use of oral contraceptives, although additional confirmatory studies are needed:

The following adverse reactions have been reported in patients receiving oral contraceptives and are believed to be drug-related:

The following adverse reactions or conditions have been reported in users of oral contraceptives and the association has been neither confirmed nor refuted:

Serious ill effects have not been reported following acute ingestion of large doses of oral contraceptives by young children. 180, 181 Overdosage may cause nausea, and withdrawal bleeding may occur in females.

The following non-contraceptive health benefits related to the use of oral contraceptives are supported by epidemiological studies that largely utilized oral contraceptive formulations containing estrogen doses exceeding 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol or 50 mcg of mestranol. 148, 149

Effects on menses:

Effects related to inhibition of ovulation:

Effects from long-term use:

To achieve maximum contraceptive effectiveness, oral contraceptives must be taken exactly as directed and at intervals of 24 hours.

IMPORTANT: If the Sunday start schedule is selected, the patient should be instructed to use an additional method of protection until after the first week of administration in the initial cycle.

The possibility of ovulation and conception prior to initiation of use should be considered.

Zovia 1/35E-21 and Zovia 1/35E-28

Zovia 1/50E-21 and Zovia 1/50E-28

The Zovia 1/35E-21 and Zovia 1/50E-21 tablet dispensers contain 21 tablets arranged in three numbered rows of 7 tablets each.

The Zovia 1/35E-28 and Zovia 1/50E-28 tablet dispensers contain 21 colored active tablets arranged in three numbered rows of 7 tablets each, followed by a fourth row of 7 white placebo tablets.

Days of the week are printed above the tablets, starting with Sunday on the left.

Two dosage schedules are described, one of which may be more convenient or suitable than the other for an individual patient.

Schedule #1: Sunday start. The patient begins taking Zovia 1/35E-21, Zovia 1/35E-28, Zovia 1/50E-21, or Zovia 1/50E-28 from the first row of her package, one tablet daily, starting on the first Sunday after the onset of menstruation. If the patient' period begins on a Sunday she takes her first tablet that very same day. The 21st tablet or the 28th tablet, depending on whether the patient is taking the 21- or 28-tablet course, will be taken on a Saturday.

Subsequent cycles:

21-tablet course--The patient begins a new 21-tablet course on the eighth day. Sunday, after taking her last tablet. All subsequent cycles will also begin on Sunday, one tablet being taken each day for 3 weeks followed by a week of no pill-taking.

28-tablet course--The patient begins a new 28-tablet course on the next day, Sunday, and all subsequent cycles will also begin on Sunday, one tablet being taken each and every day.

With a Sunday-start schedule, a woman whose period begins on the day of or 1 to 4 days before taking the first tablet should expect a diminution of flow and fewer menstrual days. The initial cycle will likely be shortened by from 1 to 5 days. Thereafter, cycles should be about 28 days in length.

Schedule #2: Day 1 start. The patient begins taking Zovia 1/35E-21 or Zovia 1/50E-21 from the first row of her package, one tablet daily, starting with the pill day which corresponds to day 1 of her menstrual cycle; the first day of menstruation is counted as day 1. After the last (Saturday) tablet in row #3 has been taken, if any remain in the first row, the patient completes her 21-tablet schedule starting with Sunday in row #1.

Subsequent cycles: The patient begins a new 21-tablet course on the eighth day after taking her last tablet, again starting the same day of the week on which she began her first course. All subsequent cycles will also begin on that same day, one tablet being taken each day for 3 weeks followed by a week of no pill-taking.

Spotting, breakthrough bleeding, or nausea . If spotting (bleeding insufficient to require a pad), breakthrough bleeding (heavier bleeding similar to a menstrual flow), or nausea occurs the patient should continue taking her tablets as directed. The incidence of spotting, breakthrough bleeding or nausea is minimal, most frequently occurring in the first cycle. Ordinarily spotting or breakthrough bleeding will stop within a week. Usually the patient will begin to cycle regularly within two to three courses of tablet-taking. In the event of spotting or breakthrough bleeding organic causes should be borne in mind. (see WARNING No. 11 )

Missed menstrual periods. Withdrawal flow will normally occur 2 or 3 days after the last active tablet is taken. Failure of withdrawal bleeding ordinarily does not mean that the patient is pregnant, providing the dosage schedule has been correctly followed. (See WARNING No. 6 )

If the patient has not adhered to the prescribed dosage regimen, the possibility of pregnancy should be considered after the first missed period, and oral contraceptives should be withheld until pregnancy has been ruled out.

If the patient has adhered to the prescribed regimen and misses two consecutive periods, pregnancy should be ruled out before continuing the contraceptive regimen.

The first intermenstrual interval after discontinuing the tablets is usually prolonged; consequently, a patient for whom a 28-day cycle is usual might not begin to menstruate for 35 days or longer. Ovulation in such prolonged cycles will occur correspondingly later in the cycle. Posttreatment cycles after the first one, however, are usually typical for the individual woman prior to taking tablets. (See WARNING No. 11 )

Missed tablets. If a woman misses taking one active tablet, the missed tablet should be taken as soon as it is remembered. In addition, the next tablet should be taken at the usual time. If two consecutive active tablets are missed in week 1 or week 2 of the dispenser, the dosage should be doubled for the next 2 days. The regular schedule should then be resumed, but an additional method of protection must be used as backup for the next 7 days if she has sex during that time or she may become pregnant.

If two consecutive active tablets are missed in week 3 of the dispenser or three consecutive active tablets are misssed during any of the first 3 weeks of the dispenser, direct the patient to do one of the following: Day 1 Starters should discard the rest of the dispenser and begin a new dispenser that same day; Sunday Starters should continue to take 1 tablet daily until Sunday, discard the rest of the dispenser and begin a new dispenser that same day. The patient may not have a period this month; however, if she has missed two consecutive periods, pregnancy should be ruled out. An additional method of protection must be used as a backup for the next 7 days after the tablets are missed if she has sex during that time or she may become pregnant.

While there is little likelihood of ovulation if only one active tablet is missed, the possibility of spotting or breakthrough bleeding is increased and should be expected if two or more successive active tablets are missed. However, the possibility of ovulation increases with each successive day that scheduled active tablets are missed.

If one or more placebo tablets of Zovia 1/35E-28 or Zovia 1/50E-28 are missed, the Zovia 1/35E-28 or Zovia 1/50E-28 schedule should be resumed on the following Sunday (the eighth day after the last colored tablet was taken). Omission of placebo tablets in the 28-tablet courses does not increase the possibility of conception provided that this schedule is followed.

Zovia 1/35E: Each light pink Zovia 1/35E tablet is round in shape, unscored, debossed with WATSON 383 and contains 1 mg of ethynodiol diacetate and 35 mcg of ethinyl estradiol.

Zovia 1/35E-21 (NDC 52544-532-21) is packaged in cartons of six tablet dispensers of 21 tablets each.

Zovia 1/35E-28 (NDC 52544-383-28) is packaged in cartons of six tablet dispensers. Each dispenser contains 21 light pink tablet and 7 white placebo tablets. (Placebo tablets have a debossed WATSON on one side and P on the other side.)

Zovia 1/50E: Each pink Zovia 1/50E tablet is round in shape, unscored, debossed with WATSON 384 and contains 1 mg of ethynodiol diacetate and 50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol.

Zovia 1/50E-21 (NDC 52544-533-21) is packaged in cartons of six tablet dispensers of 21 tablets each.

Zovia 1/50E-28 (NDC 52544-384-28) is packaged in cartons of six tablet dispensers. Each dispenser contains 21 pink tablets and 7 white placebo tablets. (Placebo tablets have a debosssed WATSON on one side and P on the other side).

Store at controlled room temperature 15°C to 30°C (59°F to 86°F).

Manufactured by

Watson Laboratories, Inc.,

Corona, CA 92880 12178-3

Revised, October 14, 1999

Zovia 1/35E-21

Zovia 1/35E-28

Zovia 1/50E-21

Zovia 1/50E-28

(Ethynodiol Diacetate and Ethinyl Estradiol Tablets, USP)

|

|